This past weekend, O514 took a break from our regularly-scheduled program to try something a little different: Twilight Imperium, by Fantasy Flight Games. First released in 1998, the current third edition of the game was released in 2005. Copies sitting on store shelves – arrogant in their extra-large boxes – have always drawn my eye, but the significant cost combined with the fact that the game was an unknown quantity (albeit a fascinating one) has long stayed my consumer’s hand.

Last week I learned that the complete game rules (as well as rules for the expansion, an FAQ and rules errata) are all available for free on FFG’s website. I printed up the documents and finally got an idea of what the game is all about. Convinced of its merit, I bought a copy and then faced my next challenge: convincing my O514 brethren that TI is a worthwhile experience. If our first day with the game is any indication, we have a winner.

O514 are no strangers to strategy boardgames. Struggling for domination of feudal Japan has become something of a Holiday ritual for us, and in our high school years we often sought to alter the course of more recent history. Many of Twilight Imperium’s basic mechanics will be familiar to veterans of these or other strategy games, but TI also introduces some very unique and interesting concepts that set the game apart.

Three to six players each randomly select one of ten different races and battle for galactic domination. Whereas every game of Axis & Allies begins with the players in the same position, Samurai Swords is always interesting because the disposition of the warring clans is different each time you play. TI takes this concept a step further and (borrowing from many European boardgames like Settlers of Catan) makes the layout of the entire board different for every game.

Players take turns placing hexagonal tiles, each of which can contain one or more elements: valuable planets, wormholes, navigational hazards (asteroid fields, supernovas or nebulas) or nothing at all. Tile placement rules prevent players from simply dumping all their good systems right next to their starting position, and so strategy begins immediately, with players trying to keep useful systems near their own homes while placing less desireable features close to their opponents.

As in A&A, not every “side” is created equal. Each race has its own special attributes that makes them play differently from the others. Some attributes are very simple; the Sardakk N’orr get to add +1 to every combat roll, for example. Other races have more complex abilities that allow them to interact with other players or certain game mechanics in special ways. The home systems (starting positions) for each race are also not all equal. Some have multiple planets, others have just one. Some are rich in Resources (used for producing units), others in Influence (used to vote in the Galactic Council). Although the starting forces for the various races are approximately equal, there are subtle but important differences. Some races begin play with multiple carriers and ground troops (useful for claiming worlds), while others get to begin with powerful dreadnoughts or numerous technologies. Fortunately, all this is summarized for you on your handy Race Card.

As play proceeds, players take it in turns to perform a single action, be it producing new units, moving fleets to uncontested systems or engaging enemies in combat. Once an action has been resolved, play passes to the next player who also gets a single action, and so on. Play continues around the table with each player getting several turns. Once a player has exhausted all of their options, they pass and when all the players have passed, the game round ends. Resources are refreshed and the cycle begins again. As the game rolls on, players will amass a collection of reserve units, tokens and cards and before long the table starts looking very busy:

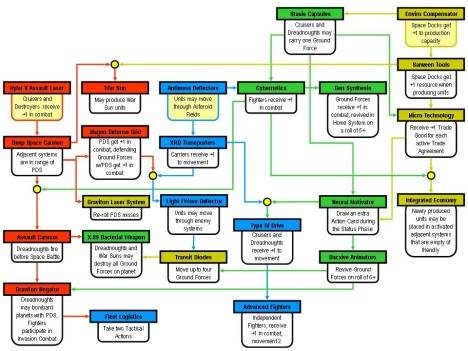

At the beginning of every round, each player also receives at least one (and in some cases two) powerful Strategy Cards which allow the holder to gain useful bonuses: free technology advances (did I mention that the game has a modest tech tree?), additional command counters (for issuing orders, among other things) or extra action cards (which generate all sorts of interesting effects). What makes Strategy Cards cool is that every time a player activates one, every other player has the option to take advantage of a lesser secondary effect. The resulting option to act even when it isn’t your turn means minimal player down-time, and it’s seldom a good idea to walk away for fifteen minutes lest you miss something.

The Tech Tree

Filed under: Games | Tagged: Axis & Allies, board games, Fantasy Flight Games, FFG, Samurai Swords, strategy, Twilight Imperium | 3 Comments »